By Peter Little

Why should we care about microplastics?

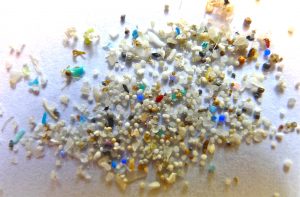

What are microplastics? The name itself gives a pretty good indication, as microplastics are simply tiny pieces of plastic. Microplastics are generally considered to be smaller than 5 millimeters and can come in a variety of shapes.

Microplastics. Photo credit: Oregon State University, https://www.flickr.com/photos/oregonstateuniversity/21282786668

The term microplastics is popping up more often because the scientific community is gaining an understanding of exactly how ubiquitous microplastics are in aquatic environments. They are found in lakes, rivers and oceans, including Canadian waters. However, the issue of microplastics in Canadian waters still isn’t well understood. For instance, the Great Lakes were only first studied for microplastics in 2012.

So what if microplastics are everywhere, is it really a big deal?

Yes, it appears that such pollution can negatively affect ecosystems. Microplastics are dangerous to organisms in two main ways. Due to their size, microplastics are often ingested by organisms and once ingested can cause internal blocking and abrasions. Chemically, microplastics have been known to absorb other pollutants found in the environment such as DDT and PCBs.

Canadian microbead ban

With the knowledge that microplastics are dangerous, has anything been done to address the problem? Fortunately, both the Canadian federal government and the province of Ontario have taken steps to reduce the impacts of one type of microplastic, microbeads. Microbeads are used in personal care products such as face washes and toothpastes. Ontario is in the process of reviewing Bill 75, Microbead Elimination and Monitoring Act, 2015, and the federal government added microbeads to the toxic substances list under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act and will begin regulation in 2018.

While these regulations are no doubt a step in the right direction, it has become apparent that microbeads are only a rather small part of the microplastic problem.

Furthermore, there are concerns over how Ontario’s legislation is drafted. Ontario’s proposed regulations will regulate microbeads smaller than one milliliter. Some commentators have criticized this threshold as inconsistent with scientific literature and therefore inadequate to address the issue. Additionally, Ontario’s regulation will still permit “biodegradable” plastics, which these critics view as no better than traditional plastics. These critics point to the fact that there is little reliable evidence that plastics labeled “biodegradable” will properly degrade in real-life aquatic conditions.

Additionally, as the US is enacting similar legislation as Canada’s, there are concerns that since the US’s legislation will be enacted six-months prior to Canada’s federal regulation, there is the potential for Canada to be a dumping ground for the outlawed microbeads during the lag period.

Regardless of these issues, the incoming provincial and federal regulations of microbeads are a positive move. There are few physical differences between microbeads and other types of microplastics, so the regulations can be viewed as a recognition of the harmful effects of all microplastics. While the focus of both the federal and provincial regulations may be on personal care products (since these products are either designed or very likely to end up in wastewater systems), it may not be too long before action is taken against other microplastics.

Is it illegal to deposit microplastics into water?

While legislators play catch-up to the real problem of microplastics, are there any other legal tools that can prevent the spread of microplastics into the environment?

One possible avenue is to show that the release of microplastics contravenes existing federal or provincial pollution statutes.

For example, could microplastics be considered a deleterious substance under the Fisheries Act, making it an offence to deposit them in waters frequented by fish?

A major difficulty in utilizing the Fisheries Act to effectively regulate microplastics pollution is that microplastics can come from a wide range of sources and are transported across bodies of water. As such, tracing the source of microplastics to a single polluter may be difficult. Further research is needed to identify sources of microplastics.

But not all deposits of microplastics are difficult to identify. For example, in 2008 a train derailment spilled tons of plastic pellets into Lake Superior, the effects of which are still being seen eight years later. For such a deposit to be considered an offence, it would need to be proven that microplastics are harmful to fish. While it is clearly understood that microplastics can cause harm to organisms, there are still uncertainties and gaps in scientific knowledge when it comes to freshwater organisms, especially freshwater fish.

Other statues beyond the Fisheries Act may be useful in combatting microplastics. Discharge of microplastics could potentially be the basis for a charge under section 14 of Ontario’s Environmental Protection Act if it is shown to cause “adverse effects”. Additionally, microplastics may be shown to be harmful to migratory birds, which would be an offence under section 5.1(1) of the Migratory Birds Act.

What else can we do in the meantime?

As for many problems, continued education and awareness-raising allow people to understand what the problem is and how to take steps to prevent it. Specifically, it will allow people to understand how their own actions contribute to the microplastic problem. Furthermore, the public can participate in public consultations and voice their concerns over microplastics.

There is also action to be taken at the local government level.

For example, while it is not clear that sewer effluent is a significant source of microplastics, municipalities may take a precautionary approach and pass bylaws regulating the disposal of any microplastic-contributing products into sewage systems.

Current action on microplastics may appear to be stagnated by uncertainties and gaps in scientific knowledge, however such issues did not prevent Canadian governments from acting on regulating microbeads. Continued pressure on all levels of government may lead to a solution to the microplastic problem.