By: Christina Persaud

The Maliseet put forth a novel “Rights of Nature” argument, opposing Mount Carleton Snowmobile Hub

In July 2015, the Government of New Brunswick announced plans to build a $1.4M snowmobile grooming hub at Mount Carleton Provincial Park. The motivation for developing this infrastructure is to promote the tourism sector, increasing the number of visitors to New Brunswick during the winter months. The trail would also extend snowmobiling season in New Brunswick by several weeks. The draft regulation amending the Off-Road Vehicle Act (SNB 1985, c O-1.5) provides that the snowmobile hub will include a fuelling station and open up 343 kilometres of new trails.

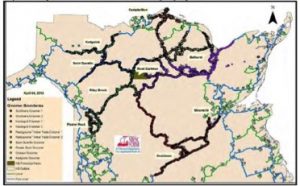

Existing groomed snowmobile trails, Northern New Brunswick (EIA Registration)

Proposed grooming trails through Mount Carleton Provincial Park (EIA Registration)

Initially, the grooming hub proposal did not have any resource management plan (required under the Parks Act, RSNB 2011, c 202 at 10.1(1)), or an environmental impact assessment (EIA) of the hub or the bridges constructed to develop the hub (required under NB Reg 87-83).

Further, the Maliseet Grand Council complained that the government did not fulfill the Crown’s duty to consult with and accommodate the Maliseet nation in putting forward this proposal.

Since then, the New Brunswick government has prepared an EIA Registration for project and in that registration, has stated that it is undertaking “significant” consultation with First Nations communities. However, the replacement of existing bridges, essential for the development of the snowmobile grooming hub, were excluded from the EIA, citing safety considerations as the primary reason for replacement, and local First Nations (the Maliseet and the Mi’kmaq) were not consulted or accommodated in this decision.

The Application for Judicial Review

The Maliseet Grand Council (also known as the Wolastoq Grand Council) brought an application for judicial review of the provincial government’s grooming hub proposal in October 2015, amended in August 2017.

In the amended application, the Maliseet Grand Council assert that the area around the bridges being disturbed is strongly tied to the Wolastoq cultural and spiritual heritage, and they provide evidence that archeological artifacts connecting the Wolastoqwiyik and their ancestors to these areas, pre-contact, have recently been discovered. Though the archeological report specifically recognised the connection that the Wolastoq have to the area around the bridges, and recommended extensive consultation with the Maliseet nation, consultation was limited to closed-door meetings and minimal information.

Questions of Treaty Interpretation

One of the issues raised in the judicial review, in assessing whether the duty to consult and accommodate was fulfilled by the provincial government, is the interpretation of the definition of “persons” in the Treaty of 1725 (Mascarene’s Promises). The Wolastoq spiritual and cultural heritage views the natural inhabitants of their ancestral lands (unceded by treaty) as “family” or “kin”, to which the Wolastoq owe a duty of care. The Wolastoq consider the language of Mascarene’s Promises to extend the protection of the treaty to the “trees, animals, air above the land, and rocks beneath the ground”. It is this interest and the rights of the natural inhabitants of Mount Carleton Provincial Park, under the Treaty of 1725 that the Wolastoq seek to represent through adequate consultation and accommodation.

In the SCC’s 2005 decision in Mikisew Cree First Nation v Canada (Minister of Canadian Heritage) (2005 SCC 69), a judicial review of a Parks Canada decision to authorise a winter road that would infringe on the hunting and trapping rights of the Mikisew Cree under a post-Confederation treaty, the Court provided guidance on the principles of treaty interpretation. The Court stated that treaties must be read in the context of their underlying purpose, as intended by both the Crown and the First Nations peoples. The Court also cited Badger ([1996] 1 SCR 771), which stated “the words in the treaty must not be interpreted in their strict technical sense nor subjected to rigid modern rules of construction. Rather, they must be interpreted in the sense that they would naturally have been understood by the Indians at the time of the signing.” Treaty interpretation in a judicial review is not a novel concept, and has been undertaken recently by the SCC. Further, other courts have ruled that in determining an application for judicial review, a court “must at least come to its own finding with respect to the [group’s] rights and the intensity of the Crown’s duty to consult it”.

Within the application for judicial review, challenges for the Wolastoq Grand Council may involve establishing Indigenous knowledge and notions of kindship with nature through the evidentiary record. Canadian courts have thus far not accorded “rights” or legal personhood to non-human inhabitants of nature, though there is strong precedent for this legal framework in other jurisdictions, such as New Zealand and India.