Authors: Kirti Vyas, Bridget Allen O’Neil, Angela Dittrich

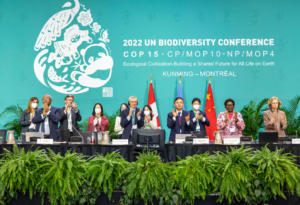

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau assured journalists at the fifteenth Conference of the Parties (COP15) to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) that Canada will meet its “25 by 25 target.”

Protecting 25 percent of Canada’s lands and oceans by 2025 is a promising step towards the more ambitious international goal of preserving 30 percent of the Earth’s lands and waters by 2030, also known as the ‘30x30’ initiative. But how will Canada meet such a bold target?

Protecting 25 percent of Canada’s lands and oceans by 2025 is a promising step towards the more ambitious international goal of preserving 30 percent of the Earth’s lands and waters by 2030, also known as the ‘30x30’ initiative. But how will Canada meet such a bold target?

Canada emphasizes partnerships with Indigenous peoples, specifically, supporting Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas (IPCAs) when affirming their commitment to this goal. The Indigenous Circle of Experts (ICE) defines IPCAs as lands and waters governed and managed by Indigenous communities for the purposes of protecting ecosystems through their laws, governance models, and knowledge systems. The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework adopted at COP15 recognizes the importance of IPCAs in achieving the 30x30 target.

Despite this acknowledgment, key concerns have been raised regarding Canada’s ability to effectively meet its commitment through IPCAs. Canada should learn from IPCA models established globally to advance meaningful reconciliation in line with the United Nations Declaration of Indigenous Peoples Act (UNDRIP) while fulfilling its international obligations.

Canada’s Approach to IPCAs

IPCAs are established in one of three ways:

- Under Crown authority,

- Self-declared Indigenous authority or

- Joint co-management processes.

In Canada, IPCAs are mainly initiated with federal funding. For example, through the “Indigenous Guardians” project, Canada invested $25 million to support 80 Indigenous-led projects from 2018 to 2022. Its Target 1 Challenge also funds projects that increase Canada’s protected areas to achieve biodiversity goals. Following ICE’s 2018 report advocating for the establishment of IPCAs, the federal government co-established its first IPCA in 2018, eventually supporting an additional 62 IPCAs.

This support, however, has been deemed insufficient by Indigenous communities, who have called on the federal government to provide long-term funding and help communities establish an institutional model that paves the way for financial independence, to support jurisdictional claims and independent governance. Indigenous communities identify a lack of provincial endorsement for IPCAs and the historical failure of colonial powers to uphold their co-governance promises as issues they wish to see resolved moving forward.

Australian IPAs – A Meaningful Model for Canada?

Following Australia’s model (referred to as IPAs) could assist Canada in meeting its international commitments to preserve nature.

Scholars have compared Canada and Australia’s models, with analysts noting that both are former British colonies with similar patterns of settler colonialism and Indigenous-led resistance.

In 1997, the Australian government established an IPA program that permits areas under Indigenous governance, or other conservation areas, to be voluntarily recognized and supported by the National Reserve System.

Similar to Canada, the federal government allocates funding to Indigenous communities to establish IPAs. The Australian government, however, continues to fund management activities under the IPA once a management plan and IPA has been recognized by the government.

The lands are either co-managed or managed entirely by Indigenous communities. Priorities for the land are set in the IPA Agreement/Management plan and are territory-specific rather than being set out in colonial federal or provincial legislation. This respects diverse Indigenous values and Indigenous authority to govern the land, while creating legal flexibility that allows the model to function in multiple settler law contexts (especially in different Australian states). Through this approach, IPAs constitute 49% of the country’s National Reserve system.

One challenge for ecological conservation in Australia is that the country’s legal framework separates land and water governance into separate legal regimes –as do many others

Indigenous communities have actively challenged this division through the IPA process, governing water and land in one system. For example, in the Bardi Jawi Indigenous Protected Area, the community receives funding to manage and monitor land and sea territory as an integrated whole.

The Clock is Ticking

Australia’s IPA approach has been endorsed by the international community, in line with achieving its CBD targets. Adopting such an approach in Canada, which respects the ability of Indigenous communities to protect the environment and their resources under their own jurisdictional authority, would support the implementation of Article 29 of UNDRIP and Canada’s 25x25 target.

As the clock inches closer to the world’s seven-year deadline to protect its resources, and climate change’s impacts continue to worsen, it is important now, more than ever, for Canada to honour the authority of, and be responsive to First Nations to achieve the 30x30 target.