One hopes the “public interest” includes the interests of encampment residents. Instead, the courts define parks as spaces for leisure activities, and judge municipal governments by their bylaw’s intentions, not by their effects.

By Nikolas Koschany

Disclaimer: The following post contains images which some may find disturbing.

Figure 1 – An encampment in Toronto’s Moss Park. Source: NOW Toronto.

This post was initially written in the winter when the snow was falling. I sat typing at a computer in a warm and cozy apartment, watching the snow gently come down. The sight is beautiful, but only from one side of the glass. On the other side, the temperature dropped to -21C, and some unhoused individuals were turned away from Toronto’s overcrowded shelters and froze to death.

This operationalization of the law – between those with and without property rights, or those with and without a place to stay – cannot be viewed neutrally when it results in people dying. This cannot, either, be understood simply as a breakdown of the shelter system. Rather, this is the broader story of systemic failure in our approach to homelessness, including how Toronto’s public space is regulated through municipal bylaws, and the injunction framework used to enforce them.

The Bylaw-Injunction Framework

Sections 608-13 and 608-14 of Toronto’s Municipal Code prevent camping, or lodging in City parks, as well as the erection of tents or structures there, except by permit. These bylaws are common across the country and are typically enforced via notices of trespass and injunctions. Municipalities argue this to be in the “public interest”. This interest may appear easy to conceptualize when preventing the unauthorized operation of a cement factory next to residential homes, but can be more complex where protecting the rights of the vulnerable (here, the homeless) requires us to rethink the status quo. Legal scholar Irena Ceric argues interlocutory (temporary) injunctions have become the legal norm for punishing civil disobedience in context of Indigenous land defense.[1] Injunctions have now also become a key legal tool in the context of encampments.

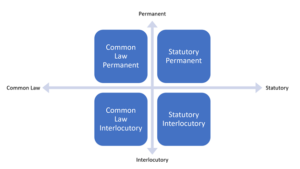

Injunctions can be sought through statutes, or the common law, and on an interlocutory or permanent basis. Where a municipal bylaw is breached municipalities often rely on statutory injunctions because they provide flexibility to prevent a wide variety of activities banned through their bylaws, beyond trespass or nuisance.

Figure 2 – Injunction Types. Original Diagram.

Courts show deference to municipalities’ conceptions of “Public Interest”

Courts have been reluctant to refuse municipal requests for statutory permanent injunctions. In Maple Ridge (District of) v. Thornhill Aggregates Ltd, the British Columbia Court of Appeal goes as far to say “[i]f the public interest is engaged and a permanent injunction is being sought, the court's only role is to determine whether a defendant has breached the by-law the municipality seeks to enforce”; the public interest here is defined as “having the law obeyed” (para 9, emphasis added). While litigants may raise Charter arguments about the constitutionality of a bylaw, a recent case from Vancouver acknowledged the “severe practical and financial barriers” encampment residents fact in bringing Charter claims (para 167-168).

More often however, municipalities apply for interlocutory (temporary) injunctions. Where a potential Charter violation is raised in the context of an interlocutory injunction (and thankfully courts have become better at reading these provisions in) the applicable test for is set out in a case called RJR MacDonald. This three-part test is well-known, and provides the court with more discretion about the “public interest”:

- There must be a serious question to be tried.

- It must be determined whether the applicant would suffer irreparable harm if the application were refused.

- The applicant must suffer greater harm than the defendant from the granting or refusal of the remedy, pending a decision on the merits – often known as the balance of convenience test.

The public interest must be taken into consideration at the balance of convenience stage. This branch of the test is “often determinative” and refers to “which of the two parties will suffer greater harm from the granting or refusal” of the interlocutory injunction (page 342). Though the Supreme Court in RJR recognized “the government does not have a monopoly on the public interest” it also held a public authority has less of an onus to demonstrate the public interest than a private applicant does (343-345). In line with Thornhill, the SCC held that the prevention of exercising statutory powers harms the public interest. In other words, only the intentions, rather than the effects, of the municipal bylaws, are considered by the courts:

“When the nature and declared purpose of legislation [or bylaws] is to promote the public interest, a motions court should not be concerned whether the legislation actually has such an effect. It must be assumed to do so. In order to overcome the assumed benefit to the public interest arising from the continued application of the legislation, the applicant who relies on the public interest must demonstrate that the suspension of the legislation would itself provide a public benefit” (page 348-349, emphasis added).

The RJR test is not concerned with an “extensive review on the merits” of the case, given these issues are meant to be raised at trial for the full injunction proceeding. Thus, many injunction proceedings do not include full consideration of Charter claims (see link).

Click link for interactive table of encampment cases.

In 75% of cases examined involving interlocutory injunctions, these injunctions ended up being the final ruling from the court – in many cases, municipalities never pursued a permanent injunction once the encampments dispersed. Thus, the merits (and consequences) of many cases are never considered.

Who are the parks really for?

The “public interest” often facilitates displacement, prompting the question whether parks are for everyone, or just those who already have property rights.

In Black, Justice Schabas ruled “the public interest purpose of [Toronto’s anti-camping] by-law, to make parks available to everyone, outweighs the interests of the [encampment residents]” (para 143, emphasis added). Despite establishing a serious question about s 7 and s 15 Charter rights violations, encampment residents lost their bid to stop the City from enforcing anti-camping by-laws during COVID-19. Once enforcement started, fences went up around some of these parks, thus preventing their use by anyone.

In numerous encampment cases the “public interest” has justified unconstrained destruction of personal property and authorization of brutal force against encampment residents and their allies during police enforcement (figure 3).

Figure 3 - Photo by Nick Lachance of encampment evictions at Lamport Stadium in Toronto in Summer 2021.

In Hamilton, a Bylaw Enforcement Protocol to deal humanely with encampment residents, was withdrawn to wide criticism in August 2021 in favour of enforcement and displacement. An injunction filed to prevent municipal bylaw enforcement failed on the balance of convenience test when Justice Goodman took into consideration the increase in crime in the parks, but failed to consider if this simply represented a shift in where crime was taking place. Put another way, the court was concerned over crime in parks, but not in the shelters it was forcing homeless individuals into.

In Prince George a permanent injunction sought by the city failed because its enforcement would result in there being “no lawful way to comply” in the absence of suitable housing (para 104). Despite this, one month later, part of the encampment was illegally demolished by the city, contrary to the order, and justified on so-called park remediation.

Hamilton and Prince George show the two sides of the injunction coin. Lose an injunction, face eviction. Win an injunction, face eviction. Rather than upholding the rule of law, the courts are becoming participants in a game of rubber stamps.

Considerations of the “public interest” demand more than blind loyalty to municipal intentions. The consequences of municipal enforcement, and the effects of injunctions must be considered to make the RJR test fit for purpose in an encampment context. Otherwise, the courts may hear cases, but on the ground people will still freeze.

[1] Irina Ceric, “Beyond Contempt: Injunctions, Land Defense, and the Criminalization of Indigenous Resistance” (2020) 119:2 South Atlantic Quarterly 353–369.